To whom it may concern:

During the 2021 Kentucky legislative session, the Kentucky Hospital Association produced a one-page document of talking points related to HB92. The identical Senate companion bill, SB76, is not mentioned in the document. Kentucky Birth Coalition appreciates KHA taking an interest in this legislation and would like to take this opportunity to provide information to supplement and, in some cases, correct the statements produced by KHA. We believe that accurate information is paramount when discussing legislation. We welcome healthy debate, but we expect KHA to hold itself to a high standard regarding accuracy.

Throughout this letter we will cite the statements made on the KHA document in bold, with our supplemental information underneath.

1) The Kentucky CON program has minimal, but important, standards for entities seeking to establish freestanding birthing centers.

Perhaps the CON process is minimal for an institution such as a hospital healthcare system, but for individual entrepreneurs and hopeful small business owners, the CON process is costly and burdensome.

The last attempt to apply for a CON for a birth center was made by Certified Nurse Midwife Mary Carol Akers, Ph.D., who endured an expensive, lengthy, and litigious process beginning in 2012. Dr. Akers was halted in her pursuit to establish a free-standing birth center in Kentucky in 2017 when a court denied her a Certificate of Need. The cost of the application alone was $4263.00 in September 2012. At the end of the five-year legal battle, Dr. Akers had spent over $200,000 and dipped into her personal retirement savings. Dr. Akers’ experience has deterred all subsequent hopeful birth center entrepreneurs from attempting to obtain a CON.

2) Birthing center CON applications qualify for non-substantive review – an expedited process – where the applicant is required to demonstrate a need in the community for the facility; however, the process gives a presumption of need to these applications. Therefore, unless there is substantial evidence the facility is not needed, the application would be approved.

Despite freestanding birth centers qualifying for an “expedited” non-substantive review, the last applicant for a birth center CON spent five years in the process due to opposition from three hospitals. Even though the Franklin Circuit Court ruled that the CON should have been granted, the opposing hospitals continued to appeal the decision and outspent the applicant in the end despite there not being a single freestanding birth center in Kentucky.

3) The demonstration of service need is vitally important to keeping Kentucky’s health care costs low, since two of every three births in the state are covered by Medicaid, which is 100% funded by federal and state tax dollars.

The data showing that birth centers reduce Medicaid expenditures is clear. A 2014 study in the Medicare & Medicaid Research Review found that birth center care could reduce costs by an average of $1,163 per birth.[1] The Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns study[2] found that Medicaid recipients in the study who received care at accredited birth centers had costs that averaged $2010 less than those with similar demographics who did not receive birth center care. Every mother and infant covered by Medicaid and cared for in a birth center would result in savings for Kentucky Medicaid. Please see the linked CMS summary and bulletin regarding the Strong Start study.

4) The Kentucky CON program has been effective at keeping costs low for Kentuckians, as multiple studies and data sources show Kentucky’s inpatient and outpatient hospital costs are one of the lowest in the nation.

With no birth centers in Kentucky, it is impossible to state with certainty how access to birth centers might impact costs. Research has demonstrated that birth centers can reduce preterm births,[3] which cost an average of $58,000.[4] Birth center care also results in fewer low birth weight infants, and a significant reduction in cesarean sections, both representing huge cost savings.

According to a report from Business Insider[5], hospital fees for birth in Kentucky for 2018, not including prenatal care or postpartum care after discharge, are as follows:

- Vaginal birth with insurance: $6,111.73

- Vaginal birth without insurance: $11,242.27

- C-section with insurance: $9,055.16

- C-section without insurance: $15,150.94

The 2017 Birth Center Survey by the American Association of Birth Centers reports that the average birth center facility fee is $2,896 and newborn fee of $966.[6]

Maintaining “one of the lowest” outpatient costs in the nation cannot be a point of pride while the maternal mortality rate in Kentucky (40.8 deaths/100,000 live births) is more than twice the alarmingly high national maternal mortality rate (17.4 deaths/100,000 live births). Perinatal mortality is a crisis in Kentucky. The solution to this crisis likely involves increasing access to care, rather than continuing to limit it with the CON program while birthing Kentuckians die.

5) The CON program also assures adequate geographic and financial access of services to Kentuckians. Kentucky hospitals treat all patients, including those covered by Medicaid (which pays below cost) and the uninsured; CON helps assure that same access is afforded by services seeking to compete with hospitals.

Kentuckians have ZERO access to the care and services provided in freestanding birth centers. In fact, many Kentucky families go out of state to utilize birth centers such as the Tree of Life Family Birth Center in Jeffersonville, IN or the Baby + Co Birth Center (Vanderbilt) in Nashville, TN.

In terms of financial access, Kentucky already has Medicaid regulations in place for birth centers.[7]

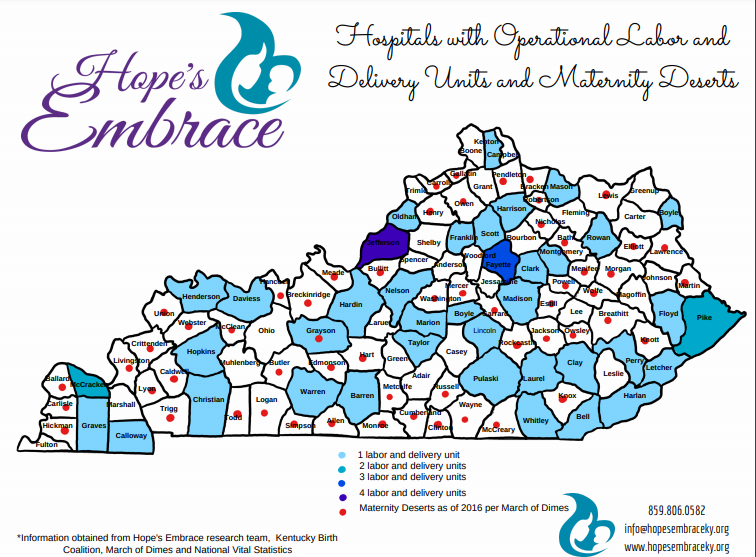

The map below, a copy of which can also be viewed here, was created through research from Kentucky non-profit Hope’s Embrace. It shows the counties in Kentucky with Labor and Delivery services as well as those identified as maternity care deserts by March of Dimes[8]. Of the 120 Kentucky counties, 81 do not have a hospital with labor and delivery, and 57 are identified as maternity care deserts. There is clearly a need for increased geographic access to maternity care in Kentucky.

6) The CON program protects the health of mothers and babies. Today, more babies are born to older women, making those deliveries higher risk where hospital resources may be needed at a moment’s notice and one in every 43 babies born in Kentucky have neonatal abstinence syndrome, where most experience withdrawal that requires intensive monitoring and care in a hospital. Kentucky has one of the highest rates of NAS (23.3/1000 births) in the nation. Birthing centers are not equipped to provide these services.

The CON requirement for birth centers effectively denies mothers and babies access to the high-quality care that is unique to birth centers. Studies[9] have shown that birth centers have an average cesarean rate of 6%, whereas a comparable low-risk population birthing in hospitals averaged a 27% cesarean rate.[10] Birth centers achieve these outcomes with no increase in maternal or perinatal mortality.

Not every pregnant person can or should be cared for in a birth center. Only those experiencing an uncomplicated pregnancy are eligible to utilize a birth center. The place for high-risk patients to birth is always in a hospital and having birth centers in Kentucky would not change this fact. Unlike hospitals, birth centers only care for patients with established prenatal care in their practice. There are no “walk ins” at the time of delivery. Birth centers screen clients before initiating care and during the pregnancy and ensure the clients are appropriate candidates for the birth center. Patients who are opiate addicted– whose newborns are at risk for Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome– are not eligible to give birth at a birth center. Medical problems that become more common with advanced age such as hypertensive disorders and insulin dependent diabetes also risk out of birth center care.

Additionally, research is clear that prescriptions of opioids after childbirth can lead to addiction and other serious opioid-related events.[11],[12] Current Kentucky statistics from the state’s Maternal Mortality Review 2020 Annual Report[13] show that 46% of maternal mortality cases had substance use disorder (SUD) linked to their death. Data provided by the Kentucky Perinatal Quality Collaborative (see here) show an alarming rate of opioid prescriptions being given to new mothers who birth in Kentucky hospitals.

Anecdotally, we know of numerous recovered mothers who have specifically sought birthing options outside of a hospital setting to avoid being faced with unnecessary pain management choices. In addition to prescriptions after delivery, epidurals, which are not utilized in a birth center, commonly contain fentanyl.[14] Pregnant Kentuckians who have overcome SUD and who are experiencing current healthy pregnancies would be well-served by the option to birth in a facility where they do not have the fear of routine interventions that could lead to relapse.

7) Licensing standards for birthing centers have been in place for many years; however, HB 92 would establish a committee of midwives – including non-nurse midwives (certified professional midwives licensed in 2019 who are not supervised by physicians) to re-write the standards, presumably to permit birthing centers to be established by these midwives, who had argued for home births.

The licensing standards for birth centers in Kentucky are outdated, having not been updated since 1990. It would be irresponsible for any facility to open without a thorough modernization of the corresponding regulations[15].

HB92 and SB76, companion bills from the 2021 legislative session, called for updated birth center regulations to require accreditation by the Commission for the Accreditation of Birth Centers (CABC) and to be consistent with the American Association of Birth Centers (AABC) Standards for Birth Centers. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists supports accredited birth centers as a recognized level of maternity care[16]. Accreditation by CABC is already required in the KY Medicaid regulations for freestanding birth centers.

The bills called for an ad hoc committee to provide input on the development of administrative regulations. The authority to promulgate regulations remains, as always, with the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. The committee includes appointees from various relevant entities which include:

- The Kentucky State Affiliate of the American College of Nurse-Midwives (APRNs)

- The Kentucky Section of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (MDs)

- The Kentucky Association of Nurse Practitioners and Nurse-Midwives (APRNs)

- The Kentucky Birth Coalition (consumers)

- The Kentucky Chapter of the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives (CPMs)

CABC accredited birth centers operate using the Midwifery Model of Care. Therefore, it is sensible that practitioners of this modality would be well-suited to provide input on regulations for facilities that will provide this model of care.

The committee would include an appointee from the Kentucky Chapter of the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives. Certified Professional Midwives are licensed by the Kentucky Board of Nursing. Both APRN Certified Nurse Midwives and Licensed Certified Professional Midwives are primary maternity care providers. Neither are required by Kentucky law to operate under supervision of physicians. While only CPMs are specifically trained in out-of-hospital care, it is within the scope of physicians, CNMs, and CPMs to practice in freestanding birth centers.

Any entrepreneur, including CPMs or non-medical professionals, could attempt to open a freestanding birth center in Kentucky under the current regulations. No “re-write” or regulation changes are needed for this to occur. However, the CON requirement is currently preventing all interested parties, including CPMs, from opening a birth center.

Home birth, which is a separate topic, has always been legal in Kentucky. No one in memory has ever “argued for home births” as far as we are aware. What was fought for and achieved in 2019 was integration and licensure of CPMs as championed by the Kentucky Birth Coalition (KBC). We are a grassroots coalition comprised of families who advocate for increased access to maternity care options in our state. CPMs did not spearhead the drive to be licensed in Kentucky. Families having home births and wanting access to licensed, competent care providers did.

The Kentucky Birth Coalition was originally named the Kentucky Home Birth Coalition, but “home birth” was never our true mission. Hence, the name change to better reflect the mission. Not every person who is seeking an alternative to a traditional hospital birth wishes to have a home birth. Thus, Kentucky Birth Coalition is now championing access to freestanding birth centers per the desires of our members. We are proud to work alongside other organizations such as Frontier Nursing University, the Kentucky Affiliate of the American College of Nurse Midwives, the Kentucky Association of Nurse Practitioners and Nurse Midwives, the Kentucky Chapter of the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives, and others to increase maternity care options in our state.

8) Other states, with weak oversight of birthing centers, have reported infant deaths in freestanding birthing centers that are independent of hospitals. Kentucky should not loosen its oversight by repealing CON or re-writing its licensure standards for birthing centers.

HB92 and SB76 would unequivocally strengthen requirements for Kentucky birth centers by modernizing the licensure requirements and requiring CABC accreditation. One can only claim that the CON makes birth centers in Kentucky “safer” by way of ensuring that there are no birth centers in Kentucky.

The unfortunate fact is that infant deaths occur in all settings, including hospitals. There is no setting, ever, where birth occurs with zero risk. According to the CDC[17], Kentucky’s infant mortality rate is 5.8 infant deaths per 1000 live births with more than 98% of all births occurring in the hospital setting. Data from the National Birth Center Study II found low fetal (0.47/1000 births) and newborn (0.40/1000 births) mortality rates in freestanding birth centers and were comparable to rates for comparable low-risk births in hospital settings. There were no maternal deaths.9

Should you have any questions regarding this information, please contact me at your convenience. Kentucky Birth Coalition looks forward to continuing accurate and robust discussion of freestanding birth centers in the Commonwealth during the interim.

Sincerely,

Mary Kathryn DeLodder

Director

[1] Howell, E., Palmer, A., Benatar, S., & Garrett, B. (2014). Potential Medicaid Cost Savings from Maternity Care Based at a Freestanding Birth Center. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review, 4(3), E1–E13. https://www.cms.gov/mmrr/downloads/mmrr2014_004_03_a06.pdf

[2] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020). Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/strong-start

[3] Alliman, J., Stapleton, S. R., Wright, J., Bauer, K., Slider, K., & Jolles, D. (2019). Strong Start in birth centers: Socio-demographic characteristics, care processes, and outcomes for mothers and newborns. Birth (Berkeley, Calif.), 46(2), 234–243. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/birt.12433

[4] March of Dimes. (2019). 2019 March of Dimes report card for Kentucky. https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/tools/reportcard.aspx?reg=21

[5] Hillary Hoffower, H., & Borden, T. (2019). How much it costs to have a baby in every state, whether you have health insurance or don’t. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-much-does-it-cost-to-have-a-baby-2018-4#kentucky-17

[6] American Association of Birth Centers. (2017). AABC Birth Center Survey Report.

[7] Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Department of Medicaid Services. Provider Information and Resources. Birthing Centers – PT (73). https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dms/provider/Pages/BirthCenters.aspx

[8] March of Dimes. (2020). Nowhere to go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the U.S. 2020 Report. March of https://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/2020-Maternity-Care-Report.pdf

[9] Stapleton S, Osborne C, & Illuzzi J. (2013). Outcomes of care in birth centers: Demonstration of a durable model. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2013. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jmwh.12003/full

[10] Dekker, R. (2013). Evidence Confirms Birth Centers Provide Top-Notch Care. American Association of Birth Centers. https://www.birthcenters.org/page/NBCSII

[11] Osmundson, S. et al. (2020). Opioid Prescribing After Childbirth and Risk for Serious Opioid-Related Events: A Cohort Study. Annals of Internal Medicine. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M19-3805

[12] Peahl, A. et al. (2019). JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197863. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2739048

[13] Maternal Mortality Review 2020 Annual Report. (2020). Kentucky Department for Public Health. Division of Maternal and Child Health. https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dph/dmch/Documents/MMRAnnualReport.pdf

[14] Novikov, N. Melanson, S. Ransohoff, J, & Petrides, A. (2020). Rates of Fentanyl Positivity in Neonatal Urine Following Maternal Analgesia During Labor and Delivery. The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine, Volume 5, Issue 4, Pages 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfaa027

[15] Kentucky Administrative Regulations. 902 KAR 20:150. Alternative birth centers. https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/kar/902/020/150.pdf

[16] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2019). Levels of Maternal Care. Obstetric Consensus No. 9. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 134, e41-55. https://www.acog.org/en/Programs/LOMC

[17] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infant Mortality Rates by State. (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/infant_mortality_rates/infant_mortality.htm

2 comments